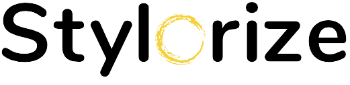

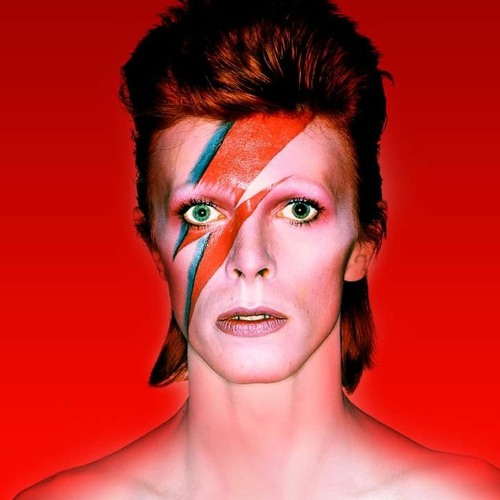

The Ziggy Stardust haircut wasn’t just a hairstyle. It was a declaration. A bright red, gravity-defying shock to the early 1970s system that announced something new had landed on Earth, and it didn’t care about your rules.

When David Bowie stepped onstage in 1972 as Ziggy Stardust, the hair did as much talking as the music. Sharp where everyone else was soft. Artificial where the culture prized “natural.” Androgynous at a time when men’s grooming still lived in safe, boring lanes. Today, the Ziggy stardust haircut is still referenced, copied, debated, and revived proof that hair, when done right, can rewrite culture.

This is the real story behind the cut: how it was made, why it mattered, and how people are still trying (and often failing) to recreate it more than 50 years later.

Why the Ziggy Stardust Haircut Hit Like a Meteor

Context matters. In the early ’70s, rock hair meant denim, long, loose, vaguely unwashed hippie hair. Bowie wanted out. He didn’t want “authentic.” He wanted alien.

The Ziggy stardust haircut was intentionally unnatural. It sat somewhere between a shag, a proto-mullet, and a fashion editorial accident that somehow worked. Short, chopped, and spiked at the front. Tight around the sides. Longer at the nape, tapering down the neck like a warning sign. And then there was the color, an aggressive, flaming red that looked radioactive under stage lights.

It didn’t whisper rebellion. It screamed it.

Bowie later said the haircut had “double the appeal” because it worked both on men and women. That wasn’t marketing spin. Fans of every gender copied it almost immediately, long before “gender-fluid fashion” had a name.

The Woman Behind the Ziggy Stardust Haircut

The Ziggy stardust haircut didn’t come from a London fashion house. It came from a small salon in Beckenham.

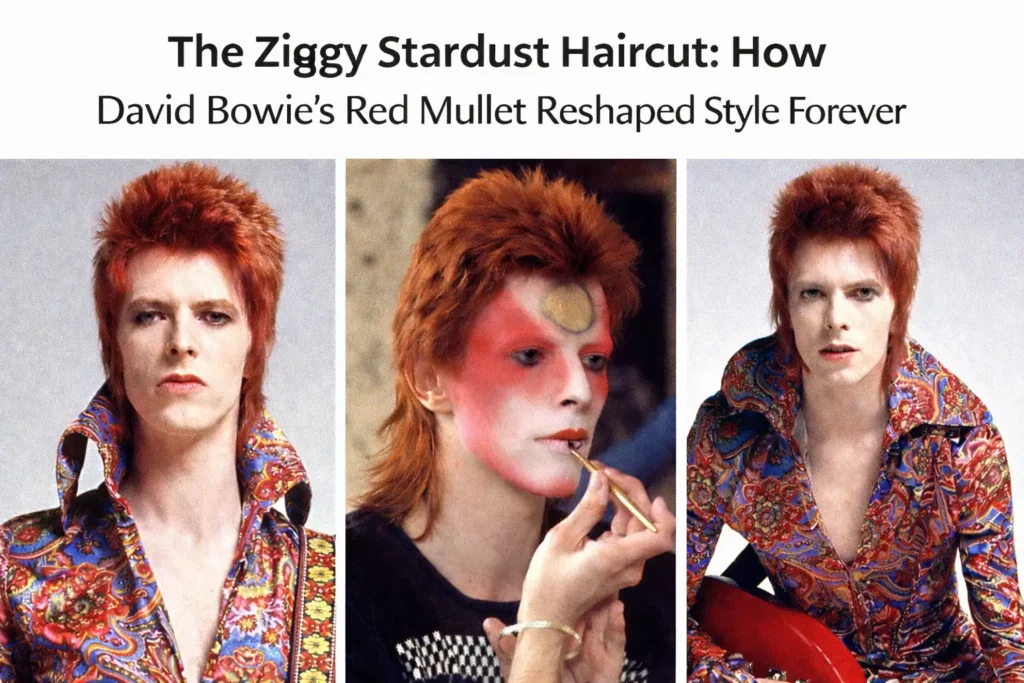

Suzi Ronson, then Suzi Fussey, was Bowie’s hairdresser and creative accomplice. In January 1972, she cut his hair short, too short, as it turned out. The first version flopped. Literally. The hair was clean, soft, and completely unwilling to stand up.

There were no modern styling products back then. No texture sprays. No volumizing powders. So Ronson improvised.

She reached for Gard, a German anti-dandruff treatment that happened to contain a setting agent strong enough to freeze hair “like stone.” It wasn’t glamorous, but it worked. Combined with deliberate chemical damage from 30-volume peroxide, the hair finally did what Bowie wanted: it stood up and stayed there.

That slightly fried, porous texture became part of the look. Ziggy hair wasn’t supposed to look healthy. It was supposed to look otherworldly.

A Haircut Built from Fashion Magazines

Despite the myth, Bowie didn’t just invent the Ziggy stardust haircut in a vacuum. It was a collage.

He showed Ronson a photograph from Honey magazine featuring a model wearing a design by Kansai Yamamoto and famously asked, “Can you do that?” The final haircut pulled its front shape from a French Vogue shoot, while the sides and back were inspired by separate German Vogue images.

That matters because it explains why the haircut feels editorial rather than practical. It wasn’t built to grow out nicely. It was built to be seen from a distance, under lights, in motion.

That high-fashion DNA is why designers still reference it today. Jean Paul Gaultier even sent identical red mullet wigs down the runway decades later, a quiet nod to how much Ziggy rewired fashion’s brain.

How the Ziggy Stardust Haircut Evolved on Tour

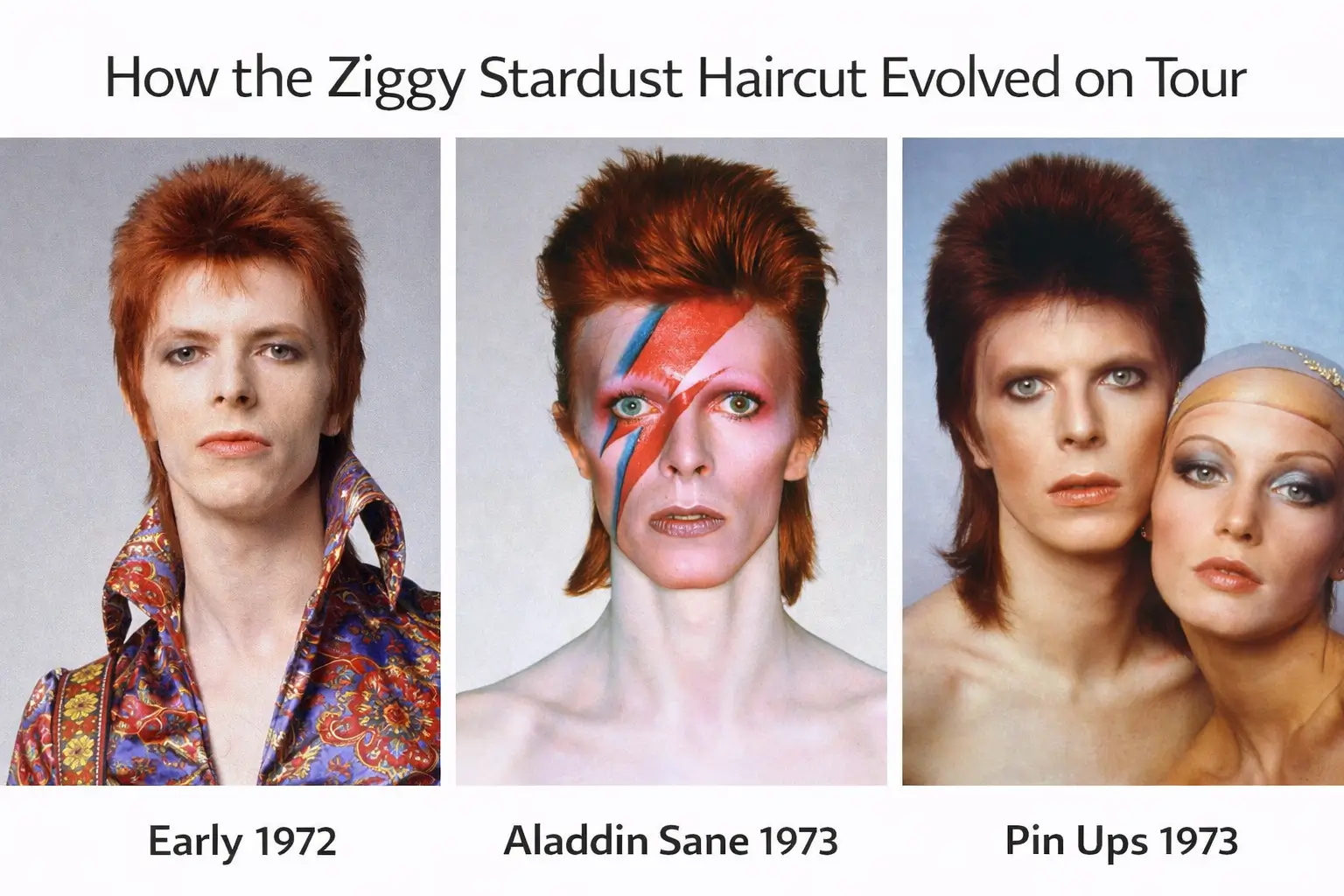

The Ziggy stardust haircut most people picture isn’t actually the first version.

Early 1972 photos show a softer, shorter shape, a little red puff at the front, very tight sides, and minimal length at the back. By 1973, during the Aladdin Sane era, the hair had grown taller, sharper, and more vertical. Bowie even shaved his eyebrows, leaning harder into the alien effect.

For the Pin Ups album cover, the hair reached its most sculpted form, deliberately contrasting with the flawless skin of co-model Twiggy. The message was subtle but clear: this wasn’t about prettiness. It was about tension.

The Ziggy stardust haircut was never static. It mutated, just like the character.

The Color That Made It Legendary

Let’s be honest: without the color, the Ziggy stardust haircut wouldn’t be half as famous.

Ronson achieved that blazing red orange using Schwarzkopf Red Hot Red mixed with 30-volume peroxide. The peroxide didn’t just lift the color; it damaged the hair enough to give it stiffness. That chemical lift was intentional.

Modern recreations often miss this. People want the shade but not the sacrifice. The result looks flat, floppy, or too polished. Ziggy hair should look slightly wrong. Too clean is the enemy.

Hair as Rebellion, Not Decoration

What made the Ziggy stardust haircut radical wasn’t just how it looked. It was what it rejected.

It rejected the idea that hair should reflect “who you really are.” Bowie believed in construction, artifice, performance. Ziggy’s hair was a costume, as important as the music or lyrics. That philosophy laid the groundwork for punk hair later in the decade, dirty, spiked, aggressive, and proudly unnatural.

You can draw a straight line from Ziggy to late-’70s punk, new wave, and even modern alt-pop styling.

Recreating the Ziggy Stardust Haircut Today

A modern Ziggy stardust haircut starts with the cut, not the color. The front needs deliberate disconnection, short, blunt layers that don’t blend politely into the rest of the head. The sides should sit close without looking faded. The nape must stay longer, hugging the neck.

Texture matters more than length. Razor work helps. So does resisting the urge to “clean it up.”

Styling today is easier than it was in 1972, but restraint is still key. Volumizing powder or sea salt spray at the roots, blow-dried upward, finished with a matte pomade or firm hairspray. Shine kills the illusion.

Maintenance is the price of admission. Roots show fast. Shape collapses without trims every few weeks. Ziggy hair is commitment hair.

The Makeup That Completed the Look

Hair alone didn’t make Ziggy alien. Makeup sealed the deal.

Bowie often collaborated with Pierre La Roche but did much of it himself. For stage, he used stark white bases and iridescent finishes. For shine on lids and lips, he relied on Elizabeth Arden Eight Hour Cream, which gave that wet, otherworldly gleam.

Modern recreations often use ultra-pale foundations like Illamasqua Skin Base SB02 to replicate the effect. The lightning bolt came later, but the philosophy stayed the same: makeup as graphic design, not enhancement.

Why the Ziggy Stardust Haircut Still Matters

The Ziggy stardust haircut endures because it represents a moment when hair stopped trying to be flattering and started trying to say something.

It proved that grooming could be art. That identity could be assembled. That a haircut could carry ideas about gender, performance, and rebellion without saying a word.

Plenty of styles look dated. Ziggy doesn’t. It still feels dangerous. Still feels deliberate. Still feels like someone took a risk and didn’t ask permission first.

And that’s why, decades later, people are still chasing that red, spiked ghost in the mirror, hoping a haircut might let them step, even briefly, into another world.